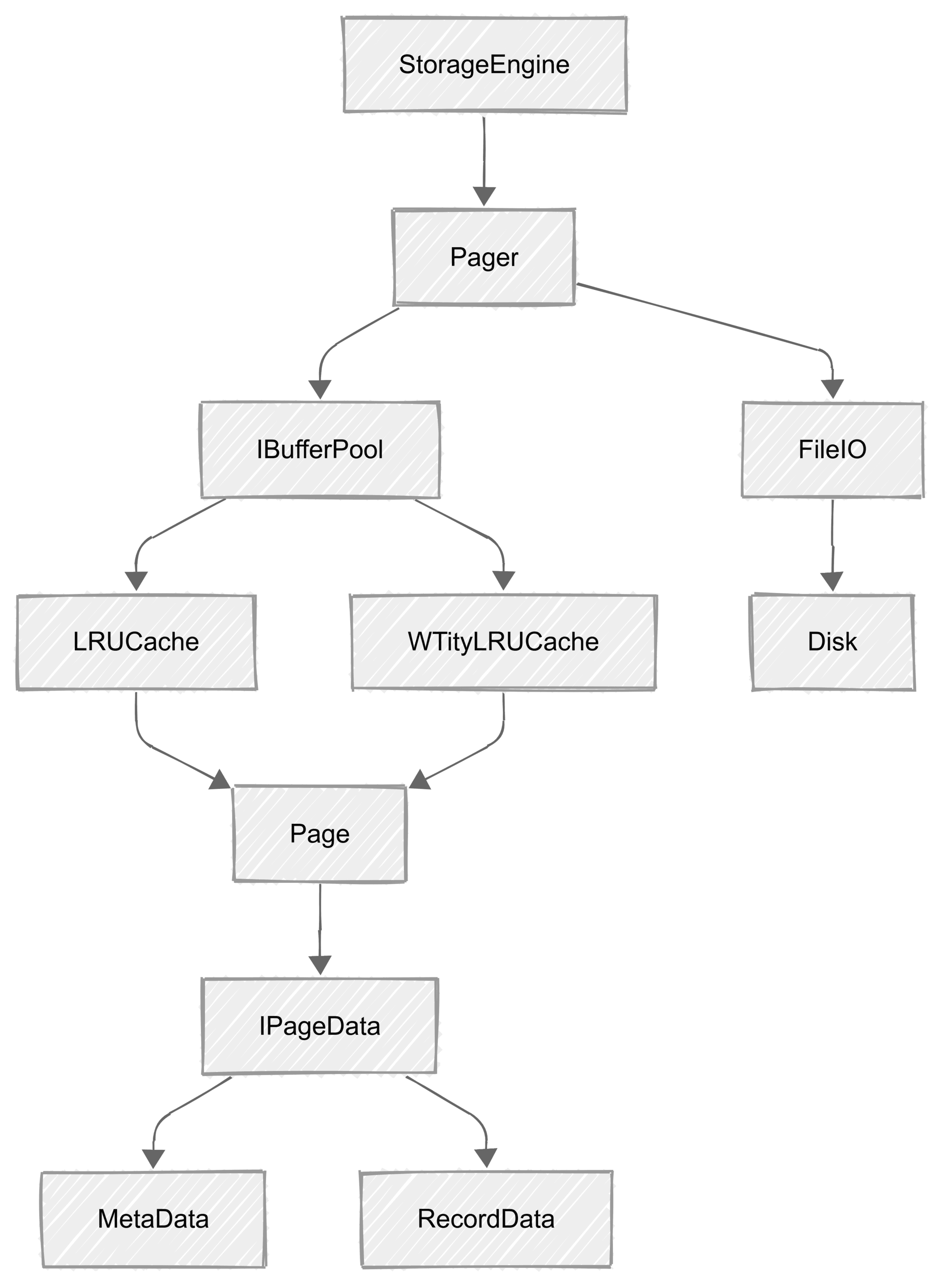

In the previous article, I explored the semantic layer—how queries are parsed, analyzed, and understood. The next logical step is to build the TableManager, which will handle table operations and data organization. But before we can implement TableManager, we need to lay the foundation: the StorageEngine. StorageEngine is the most fundamental and essential subsystem, responsible for managing how data is physically stored, retrieved, and cached. Without a robust storage layer, higher-level components like TableManager cannot function reliably.

This article will walk through the design and rationale behind the StorageEngine, setting the stage for future work on TableManager and beyond

At the lowest level, a database doesn’t store data row by row—it stores it page by page. A page is a fixed-size block (like 4KB or 8KB) that holds multiple rows, metadata, or index entries. Why do we use pages? Because reading and writing large blocks is much more efficient for disks and SSDs, and it makes space management, caching, and recovery much simpler.

The Page class is the atomic unit of storage. It has fields like:

PageType: What kind of page is this? (Meta, Data, Index, etc.)PageNo: The unique number of the page in the file.PrevPageNo / NextPageNo: These let us chain pages together, which is crucial for things like linked lists, overflow pages, or B+ trees. For example, if a table’s data spans multiple pages, you can follow the chain.Dirty: Marks if the page has been modified in memory and needs to be flushed to disk.LSN: Log Sequence Number, used for recovery and write-ahead logging.IPageData PageData: The actual contents—could be metadata, user records, etc.ReaderWriterLockSlim Lock: Ensures thread safety for concurrent access.Before we talk about why there are two data types, let’s look at the structure:

IPageData interface:

Encode(): Serialize the data for storage.Decode(stream): Deserialize data from storage.Size(): Get the size of the data.MetaData structure:

string Version: The database version.Dictionary<string, TableSchema> Tables: Table definitions and schema info.RecordData structure:

List<Row> Rows: Actual table rows.List<(int Offset, int Size)> SlotArray: Fast lookup and update for rows.byte[] Data: Raw binary data for the page.Why do we need two types? Because the structure of metadata and row data is fundamentally different. MetaData is for schema/catalog info, while RecordData is for user table rows. By designing separate structures for each, we can optimize for their specific needs and make the engine easy to extend for future types, like index pages or blobs. Both implement IPageData, so Pager and Page can handle them polymorphically.

FileIO: Bridging Pages and DiskOnce we have pages, we need to read and write them to disk. That’s where FileIO comes in. It’s responsible for:

pageNo * PAGE_SIZE, read PAGE_SIZE bytes, and decode into a Page object.These are implemented by:

Key fields:

FileStream filestream: The actual file handle.Core logic:

ReadPage(pageNo): Seek and read a fixed-size page.WritePage(pageNo, buffer): Seek and write a fixed-size page.Flush(): Flush file buffers.Why not let every module access FileIO? Because direct disk access is risky—one bug can corrupt the whole database. By centralizing disk logic, we keep things safe and consistent.

Now we need a way to manage all these pages—allocating new ones, reading, writing, and keeping track of which are in memory. That’s the job of Pager.

Pager is the only module that talks to FileIO. It knows how to:

These can be implemented by using these methods:

GetPage(pageNo): Try cache, else read from disk and cache it.WritePage(page): Encode and write to disk.AllocatePage(type): Assigns new page number, creates and writes page.Key fields:

FileIO fileIO: Handles raw disk I/O.IBufferPool<uint, Page> bufferPool: Abstracts the cache layer.Pager is the only module that knows about both disk and cache. It always tries cache first, then disk. By depending on IBufferPool, you can swap in any cache strategy.

IBufferPool and LRUBy coding to an interface, Pager can use any cache—LRU, no-cache, or custom. This makes testing and extension easy.

To solve the performance problem, I introduced the IBufferPool interface. Pager doesn’t care what caching strategy is used—it just calls TryGet and Put. This makes it easy to swap in different algorithms.

Interface:

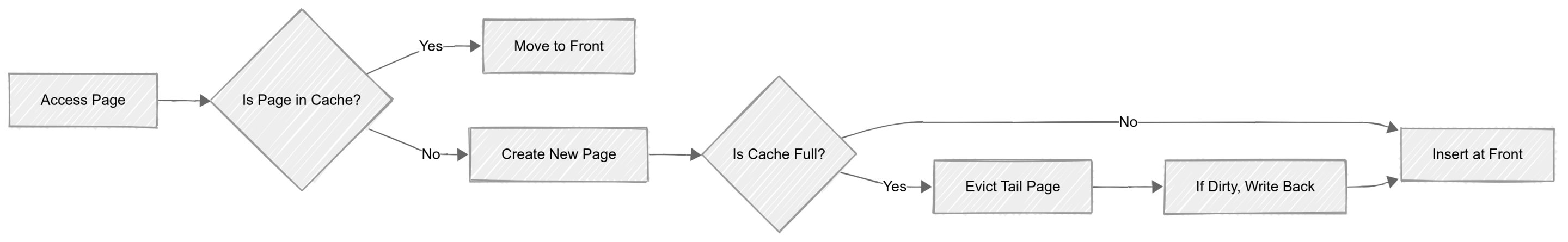

TryGet(key, out value): Query cache.Put(key, value): Insert/update cache.Close(): Cleanup.The first cache I implemented was LRUCache (Least Recently Used). Why LRU? Because it’s simple and effective: when the cache is full, evict the page that hasn’t been used for the longest time.

LRUCache DesignLRU (Least Recently Used) is a classic cache eviction algorithm. Its core idea: if data was accessed recently, it’s more likely to be accessed again soon; data that hasn’t been used for a long time should be evicted first.

LRUCache Structure

1 | class LRUCache { |

LRU is simple and efficient, and fits most database access patterns well. It keeps hot data in memory, reduces disk IO, and improves performance.

This design keeps hot pages in memory, evicts cold pages automatically, and uses the eviction callback to ensure dirty pages are never lost.

StorageEngine or other modules use the cache directly?Because caching is an optimization, not a core responsibility. Only Pager should manage page lifecycle and caching, to avoid stale data and logic bugs.

StorageEngine: The OrchestratorAt the top level, StorageEngine coordinates everything. In early designs, I let StorageEngine reference Pager, FileIO, and IBufferPool directly. But this quickly became messy—every change to caching or disk logic required changes in StorageEngine.

The right approach is to let StorageEngine only reference Pager. Pager handles all page operations, caching, and disk I/O. This keeps StorageEngine clean, focused, and easy to extend. In the future, when I add indexing, StorageEngine will also reference IndexManager.

Notice how StorageEngine now only points to Pager. This isn’t just a diagram—it’s a reflection of a cleaner, more maintainable architecture. Pager is the “gateway” to all page operations, and everything else is hidden behind interfaces and abstractions.

Throughout the engine, the theme is clear: each module does one thing, and only talks to its immediate neighbors. Direct access is avoided to keep responsibilities clear, make testing easier, and allow for future evolution.

This isn’t just theory—it’s the result of real-world pain from earlier, more tightly coupled designs. By refactoring to this structure, the engine became more robust, maintainable, and ready for new features.

When you read or write a row, StorageEngine calls Pager, which checks the cache (via IBufferPool). If the page isn’t cached, Pager loads it from disk using FileIO, decodes it, and puts it in the cache. When the cache evicts a page, the callback ensures dirty pages are written back, so you never lose data.

This modular, interface-driven design makes the engine robust, testable, and easy to extend—whether you want to add new cache types, page formats, or storage backends.

In the next part, I’ll dive into two important topics:

IndexManager: How indexes are managed, how they interact with pages and the storage engine, and the rationale behind index structures in LiteDatabase.WTinyLRU: A more advanced cache eviction algorithm compared to classic LRU, with a focus on its design, implementation, and why it can outperform traditional LRU in certain scenarios.